Over the past three years MediaWise has worked closely with many women survivors of family violence, as well as journalists, in bid to help the public understand more about the issue.

It has been, at times, an emotional journey and a steep learning curve as we work to challenge persistent myths and stereotypes.

When we first began our work, it was fairly evident that many journalists – or editors – had a mind set of blame the victim, particularly when it came to rape or sexual violence. The Slut Walk, for example, was misunderstood – with reporters writing or broadcasting the Walk in a way that seemed to suggest that the abuse against women was provoked by the way they dressed or their behaviour.

We start our interviews from the perspective that we are not here to sensationalise already extraordinary stories.

The given rule of thumb is that whatever is written must never hurt the women, they must see the stories before they are published, and any identifying material removed. The second, and equally important, rule of thumb, is that women who are still going through court should not be interviewed or photographed.

Our other tips:

Language

Use the term ‘domestic violence’ or ‘family violence’ for two reasons: firstly, if the terms are in the public domain all the time, the public will get a better understanding of the extent of the problem; and secondly, words such as dispute, bashing or volatile are trivial and minimise the violence.

Women’s safety comes first

Many survivors remain in unsafe situations and often are not aware of it. When we interview women, we spend time chatting to find out more about them now, what is worrying them, and about their story into family violence. We agree with the women what details to include, or not. Frequently we use another name to ensure her anonymity.

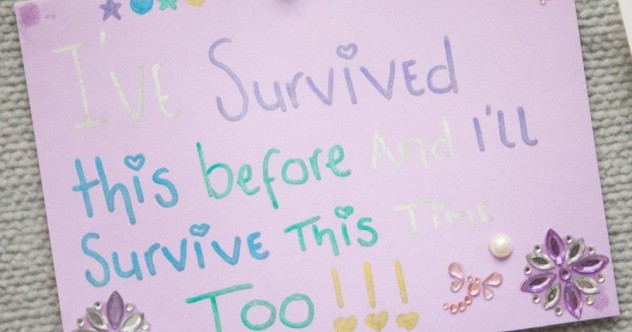

This also applies to photography. We rarely take photographs of a woman survivor’s face, but instead take photographs from behind, or of her hands, or holding something which is relevant to the story. The bottom line is check with a survivor to see what they agree and feel safe to disclose. Never put them at risk.

When we interview women, we always make sure they have access to support before and after sharing their story. We also assess whether or not to publish their story, depending on the potential danger.

Know the law

There are always certain legal parameters to follow, and make sure you know what you can report, or cannot, especially if there is a protection order in place or where children are involved.

Never accept violence

Never use language or frame a story that suggests the survivor of violence was in any way to blame for what happened to him or her. Family violence always has a survivor or victim and a perpetrator. This is important to acknowledge. Headlines such as Woman Killed or Woman Abused – with the focus on the woman – can fuel the stereotype that violence just happens to women. Turn the headline around, and highlight the role that perpetrators have.

http://www.mcauleycsw.org.au/stories/on-the-seventh-day-of-christmas-my-wish-came-true

http://www.mcauleycsw.org.au/stories/16-days-against-violence-campaign-day-10

http://www.mcauleycsw.org.au/stories/feels-like-home-to-shiara